Miscellanies and Eighteenth-Century Print Culture

Miscellanies differ from poetic anthologies in that they tend to reflect the literary taste of the moment, rather than a canonical history of poetry. In emphasizing contemporaneity and popularity in contemporary verse, miscellanies offer us snapshots of literary taste at any given historical moment. This database will make it possible to track the development of individual collections, and the ways in which publishers responded to the changing demands of their markets.

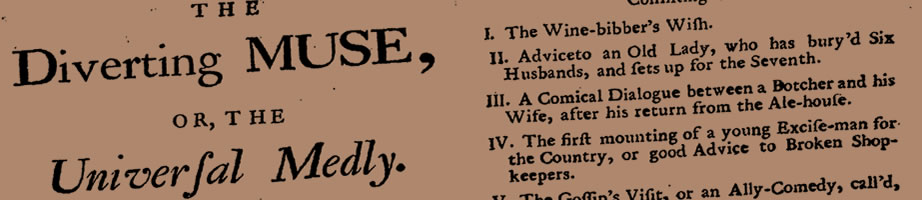

The body of miscellanies gathered within this Index shows how diverse those literary “moments” could be. One of the things these collections illustrate is the heterogeneity of literature and music in the period, and its fusions of high and low culture: eighteenth-century readers were happy to view bawdy or scatological poems alongside pastoral love lyrics, and imitations of Horace, within the same miscellany. But the collections are also diverse generically: the collections we have gathered run from comic, political, romantic, location-specific, satirical to educational. The range of their titles shows something of this range: from Dirty dogs for Dirty puddings (1732) to Elegant Extracts (1789), or Poetical Blossoms: or the sports of genius, by the young gentlemen of Rule's Academy at Islington (1766) we can see that consumers bought and used these collections to very different ends.

Many of the titles listed offer a variation on the theme of a collection of the flowers of verse, that is, small choice poems, a meaning derived from the Greek word anthology. Another recurring trope is that of the “Museum”: again, alluding to Hellenic models of cultural collection, and in particular, to a building connected with or dedicated to the Muses or the arts, or inspired by them. Other collections use their titles to suggest the intimacy of a personal collection of verse: “A Pacquet from Parnassus”, “The Lovers” Pacquet”, “The Ladies Cabinet Broke Open”. Here, the printed miscellany seems to be compared with collections of manuscript sources, such as familiar letters or commonplace books.

All these publications offer insights into the print culture of the period. Critical trends of the last thirty or so years have seen a huge rise in interest in non-canonical, little-known, yet often highly important areas of poetry. Many poems in this period were published individually, but went on to enjoy an afterlife in the miscellany culture of the period. Scholarship concerned with poetic reception still relies largely upon the same handful of anthologies and miscellanies for evidence of popularity of individual poems or authors, particularly with regard to well-known collections like Robert Dodsley”s six volume Collection of Poems by Several Hands (1748-1758) or Thomas D”Urfey”s Pills to Purge Melancholy (1719). It is impossible to map the development of the literary canon and the changing nature of eighteenth-century poetics using such a tiny sample as an index of popular taste. This database will, where possible, record every poem in every surviving miscellany in the eighteenth century (of which there are almost a thousand). In doing so it will enable researchers for the first time to ask very precise questions about texts, readers, and publishers, and to use that information to map the often unpredictable shape of eighteenth century poetic culture.